Places of interest

Places with history and beauty

Places of interest

A corner of paradise on earth.

With thermal springs not too far apart, but quite different in the waters that flow from their depths, both provide important benefits for the body’s health. Boñar offers its healing waters to the visitor, but also a natural, cultural and historical heritage that fills all the senses and the imagination of the visitor. These are places of public interest where you will always find unique settings, the solitude you are looking for or meet authentic, very friendly people with endless sympathy.

The Calda Fountain

The Roman inscription says:

“To the genius of the Agineese fountain, the man freed from Vispaca of Brocco, the heretic Alexis, gladly fulfilled the promised vow”.

Located on the northeast face of the peak of La Salona.

Its waters flow at 26ºC, releasing oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrogen. Its most concentrated element is magnesium, along with iron, zinc and lithium. 50 l/s flow from the fountain.

Included since 1892 in the Monograph of mineral and thermal waters of Spain, it was granted the title of public utility by Royal Decree on 16 January 1907.

Its indications are as follows:

Muscular, joint and especially uretic rheumatism, liver infarction, cystitis, gastric and intestinal disorders, nutritional deficiencies and dermatosis linked to nutritional deficiency.

In 1097, a famous spa was built next to the spring, which is no longer in use.

Currently, the spring of these thermal and medicinal waters is not exploited in any way.

Fuente de la Salud

Located about 150 metres from the La Calda spring. It was first documented in 1765. It has a monolith erected in 1868 with a Latin inscription that reads:

“Heals chlorosis

and cleanses the clogged liver

with mild diuretics

freeing us then

of the ailment”.

Trace elements (mg/l): Iron, 1,500 / Magnesium, 80 / Copper, 70 / Zinc, 30 / Boron, 1,500 / Lithium, 430.

Spring classification: ferruginous, sulphate-bicarbonate, calco-sodic water.

Indications: Rheumatism, traumatology, skin, digestive and respiratory system.

Puente Viejo or San Pedro bridge

14th century bridge

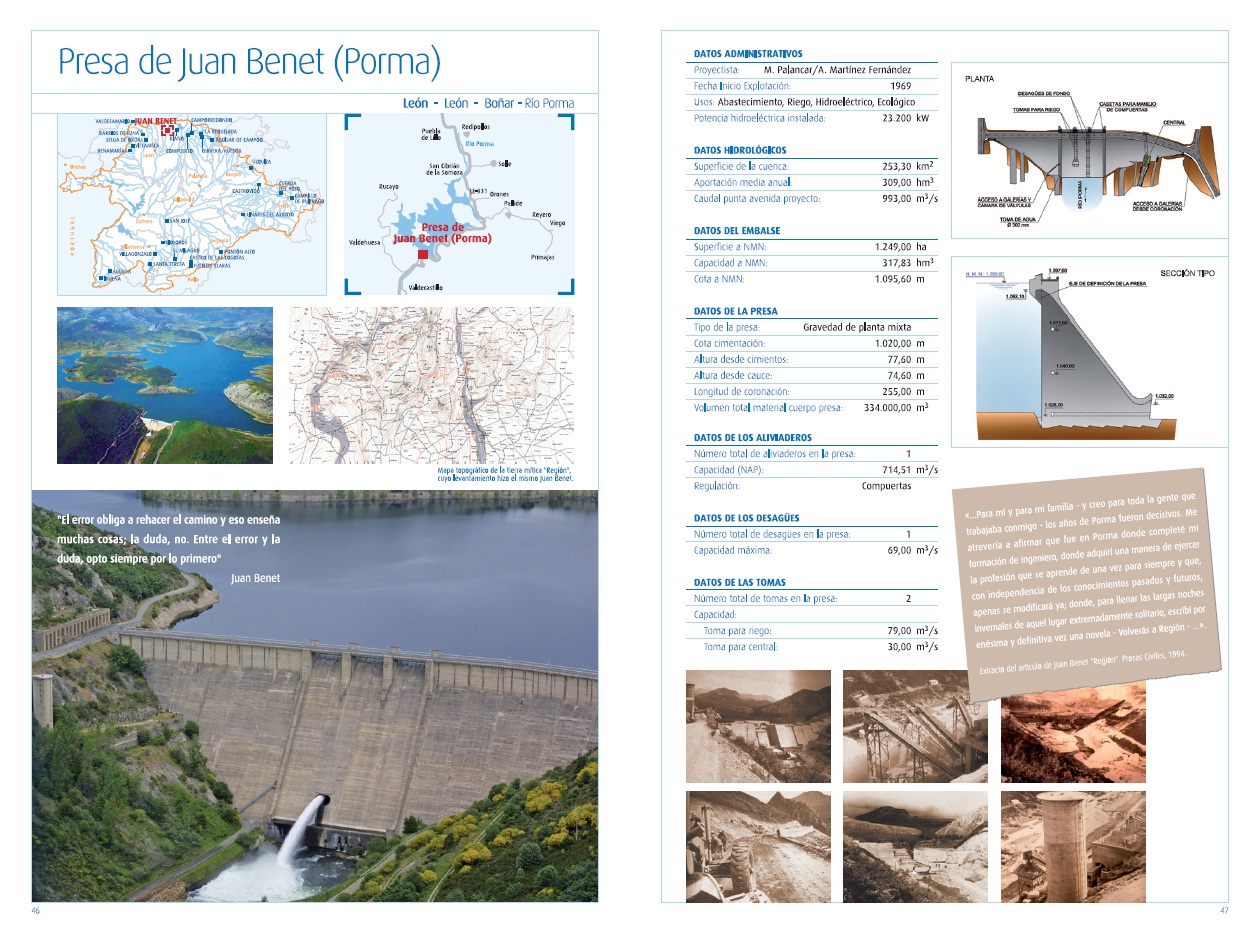

Porma Dam

Porma or Vegamián Dam:

This dam plays a fundamental role in the regulation of the rivers of León and its capacity has made it possible to reduce the risk of numerous floods in the lands located hundreds of kilometres downstream, including the region of Benavente, in the province of Zamora. Also known as Vegamián, it is located just 10 kilometres from the town of Boñar and less than 60 from the capital, León.

The concrete wall that encloses it bears the name of the engineer and writer Juan Benet, who worked on it during its construction. The dam is more than 250 metres long at its top and around 345,000 cubic metres of concrete were used to build it. This large reservoir, irrigates around 45,000 hectares of land and a wide variety of water sports, except motor boating, can be conducted in its waters. Its open location facilitates the entry of winds in all directions, which makes it an unbeatable place for sailing sports, which is why the Junta de Castilla y León has established its Nautical Sports School here.

Current map of the Porma Dam

Map of the Porma Dam 1915-1960

Pardomino Forest

Located in the southern mountain range of the Sierra del Mampodre, the Pardomino Forest is a mixed forest mass (surface area: 2,022 hectares) of great diversity. In this forest, there are sessile oak (Quercus petraea), oaks (Quercus pyrenaica), beeches (Fagus sylvatica), birches (Betula pubescens ssp. celtibérica), European ash (Fraxinus excelsior), English holly (Ilex aquifolium), Quercus robur, etc.

Pardomino

The forest is located on both slopes of the Barranco de Pardomino, at altitudes of up to 1,500-1,600m above sea level, with a notable stratification of trees, although always in mountain environments with a marked Mediterranean influence.

In degraded areas or as the first stages of vegetative replacement, there are pyornales, escobonales and heaths, and Cytisus scoparius, Daboecia cantabrica, Erica aragonensis, etc., can be mentioned as typical of these areas.

Nestled in the Pardomino Ravine, the area also includes the slopes and lateral tributaries of the stream of the same name; it extends south from Pico Redondo following the limits of the Natural Area to the municipal boundary line that separates Boñar and Crémenes, running along it to the Alto de Tierra la Mula (1,564m), from where it goes to Pico Laceo (1,587m), continuing on to La Capellana.

La Capellana

Once here, it follows the watershed that delimits the basin of the Pardomino stream to the north, where Las Piedras de Requejo and Peña de San Pedro are located, up to 1,250m, to the southeast of the PK. 11 of the road from Boñar to Puebla de Lillo.

Puebla de Lillo

From here it descends along the watercourse to the bridge that crosses the Pardomino stream, then descends along the right bank of the stream to the ridge that rises to 1,172.3m and continues to the Pico Candanedo. Once there, it descends through the firebreak to the path that goes down to the La Lobera pass from where it climbs up to Pico Redondo, the starting point of these borders. The best time of the year to visit the forest is autumn, for the variety of colors it displays.

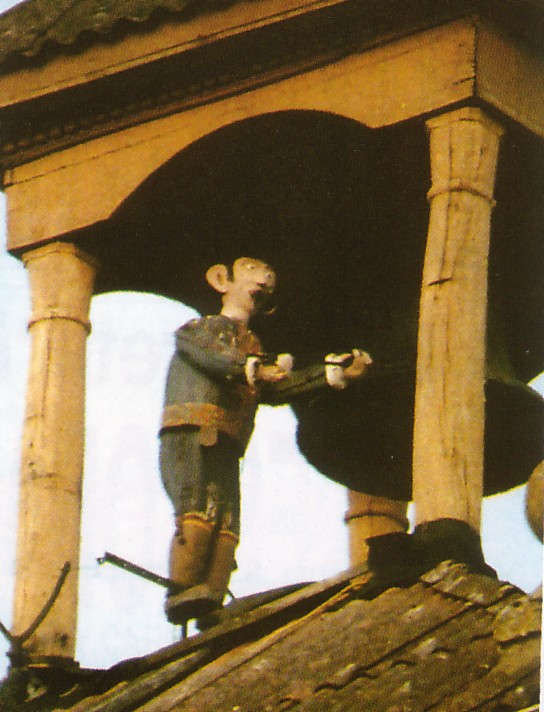

‘El Maragato’ in the Tower

Excerpt from the book “Boñar – Recopilación de datos para una historia” by Manuel García Ripado. ” … In 1925, the engineer from Talcos, Bernardo Crosa, came up with the idea of finishing off the church tower with the typical “maragato” that, synchronized with the clock, would sound the hours with a hammer. And so it was done. He was assisted with the good work of Desiderio Cañón, a local carpenter. From a pear tree, they say, from Doña Tomasa’s orchard, he carved that famous doll.

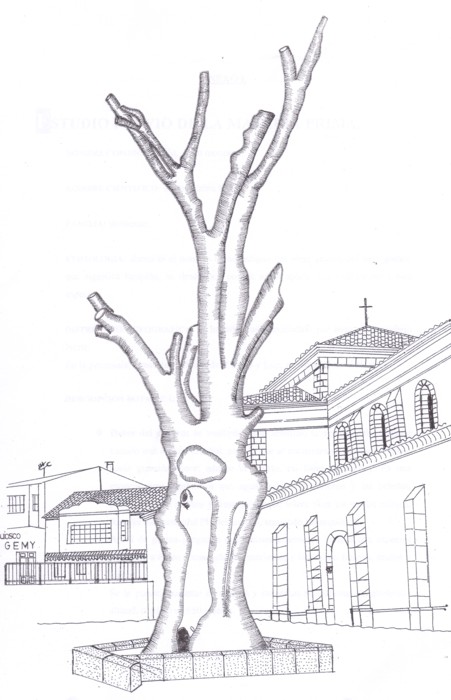

El Negrillón

This huge negrillo was dated in 1574, when Suero Alfonso was the parish priest of Boñar.

The Negrillon, emblematic specimen of the province, began to fall ill in 1980 due to Dutch elm disease, a disease which originated in the Pyrenees.

Every possible measure was then taken to keep it alive. The disease affected the bark, which went into a serious process of deterioration, a situation aggravated by the lack of irrigation in the roots and the loss of leaves.

It was in the 1990s when the Negrillon was finally declared lost and stood upright until Tuesday, January 5, 2016, when it has finally fallen down.

However, the Negrillón de Boñar is still the symbol of this town.